Is Donald Trump's Star Power Finally Fading?

Talking with "New York Times" TV critic James Poniewozik about how Kamala Harris hijacked Trump's Main Character Energy.

Back in the 2000s heyday of The Apprentice, I used to interview Donald Trump regularly for Entertainment Weekly magazine. I called him often—he was always good for a quote (and, in fact, I still have that office number stored in my phone).

A few times, I visited him in his Trump Tower office for a lengthier interview. He had kind of a ritual for interviews, which I know was consistent no matter who the interviewer was, because I’ve read many other journalists’ accounts of the experience since: He’d greet you by name and use direct address a lot. He’d often give you some kind of handout that he had ready to show how great he was, like a recent profile in Crain’s New York Business. He’d flatter your appearance one way or another. One time he took what I swear was a pretend phone call with his daughter, who was allegedly checking in with him from a ski trip, and he said, “Okay, honey, I have to go now, because I have a young lady in my office who’s almost as beautiful as you.” I cannot prove that this was only an act, but I will die believing it was.

When Trump was starring on The Apprentice, he was finally doing what he was meant to—not selling real estate, not “businessing” in the generic sense that he pretended to do on The Apprentice, but entertaining.

He would lie to my face often, and I knew it was happening. “Jennifer, as you know, we are the No. 1 television show of all time.” No, I literally reported TV ratings in the magazine every week, so I knew down to the decimal point what the ratings were and that they were not that. But at that time, his lies were inconsequential, all part of his character.

Never, ever did I imagine that this man I talked to (and laughed at) regularly in my job as an entertainment reporter would become president of the United States. That’s why I felt such a connection to New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik when I interviewed him recently about Trump. We both said the exact same thing: Why would anyone we covered as entertainment reporters (he, at the time, was at Time magazine) become a history-changing (for the worse) world leader? It felt like a support group for former Trump interviewers.

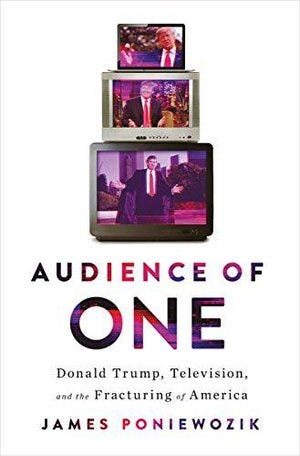

But Poniewozik has also spent a lot of time since then studying Trump as, specifically, a media star for his brilliant 2019 book Audience of One: Donald Trump, Television, and the Fracturing of America. It’s a cogent and infinitely readable analysis of how and why Trump exists as the phenomenon we now know him as—infuriating, watchable, inescapable.

I thought of this book again during this election cycle, however, because I felt a shift as Harris took over the Democratic nomination from her predecessor Joe Biden, and also, quite surprisingly, snatched the news cycle from Trump and hasn’t let up since. Has Trump finally lost the ability to hold our attention? Have TV and the media landscape changed enough in the last decade or so to finally make his act look tired? If anyone has the answer, it’s Poniewozik.

We both said the exact same thing: Why would anyone we covered as entertainment reporters become a history-changing (for the worse) world leader? It felt like a support group for former Trump interviewers.

At times, it has seemed as if the Harris-Walz campaign is using Audience of One as an actual playbook, undercutting his fearsome “antihero” schtick, as Poniewozik explains it, with simple mockery, calling Trump and his running mate J.D. Vance “weird.” Harris expertly used Trump’s desire to play to the cameras against him in their televised debate, goading him into meltdown after meltdown.

And at the Democratic National Convention, the party counterprogrammed Trump’s brutalist version of masculinity by staging a Friday Night Lights-style rally for football coach-turned-vice presidential candidate Walz; Audience of One calls the inclusive team-building of Friday Night Lights out by name as the antithesis of Trump’s us-versus-them mentality. Poniewozik has been astutely cataloguing it all in his reviews of debates and conventions, as important an analysis in the modern world as coverage of policy or polls.

Here, my conversation with Poniewozik about whether Trump’s star power is waning this election cycle, how the Democrats finally (maybe) learned to counterprogram him, and what it might take to defeat him at last.

JKA: I wanted to talk to you because I've been thinking a lot about Trump's star power in this particular election cycle. What is your read on this?

JP: Before I talk about it in this particular election cycle, I need to talk about it in general, which is that as critical as anybody might be about Donald Trump for this, the fact is you don't get elected president by not being good at anything. He may have flaws as a leader or a role model or a businessman compared to what he says his successes are, but he is amazingly good at understanding just viscerally how the media works.

He's just somebody who has been on television a lot and knows how to hit his marks and knows that often how you look on a screen is more important than what you're saying. But also just this one thing I wrote a lot about in my book is that his brain thinks like a TV camera. He has a sense of what live television wants, its need for incitement and some new thing to attract attention, and he knows how to give it that, and that served him well before he was in politics. He was, again, to the extent that he was successful as a real estate developer, he was successful largely because he made himself into a celebrity in the 1980s. He was very good at branding and he figured out how to leverage celebrity and the value of a name into something that people would pay money for, and then ultimately he applied that to his campaigns.

And without re-litigating the whole 2016 election, one thing that worked really well for him in the primary and then in the general election was that in the electronic media era, elections want a protagonist. There's a person who the election is about and other people are responding to that person and talking about things in terms of them, and you're thinking about what they will do or how somebody else will react to what they do.

Obama was that. This is not something that Trump invented, but he, with his rallies and just the whole persona and the insults and the racist statements and what-is-he-going-to say-next and all that, he literally got himself billions of dollars in earned media, and that was not irrelevant in him winning that election.

[Trump’s] brain thinks like a TV camera. He has a sense of what live television wants, its need for incitement and some new thing to attract attention, and he knows how to give it that, and that served him well before he was in politics.

Now, when you talk about his star power in this election, I think at this point, almost a decade later, it's become kind of weird and more complicated because it's an advantage to be the protagonist of the election, but that's not necessarily the key to winning. I would say that he was also the protagonist of the 2020 election and lost it for some of the same reasons that there was focus on him, and it ended up being negative attention to the extent that Joe Biden just ran as the mute button. I think it's a rare situation in politics where you can counterprogram something with nothing and have that benefit you, but I think in that case it did.

JKA: It does seem like the Democrats finally caught on after three cycles with this guy of the ways that he uses media and maybe started to actually try to beat him at his own game a little bit. Why do you think it took so long for people to adapt to him?

JP: There are a few factors. One is that Joe Biden was never the candidate who was going to beat him at his own game, right? He may have won in 2020 for that reason. But nonetheless, in the 2020 primary, the Democrats rejected a lot of their more mediagenic candidates who you might have imagined becoming counter-media celebrities to him, whether it was Kamala Harris or Beto O'Rourke or Pete Buttigieg.

Part of the problem is that you have to figure, you can't just be Donald Trump against Donald Trump. Because his persona and his way of monopolizing the camera, it's a thing that's particular to him, and if you just try to imitate him, you look like a weak imitation, but also in some ways, it particularly appeals to the Republican party and his own MAGA movement within it.

In other words, a lot of the stuff that's like the performative masculinity and appeals to strength, then the idea of life as a conflict and dominance and all that, those are not necessarily the themes of the modern Democratic party. Obama was famously a mediagenic politician, but he wasn't like Donald Trump. I think that partly just due to Joe Biden's fortuitous implosion in the debate in June, the Democrats ended up with another ticket that seems like they could do a kind-of Democratic version of that, which is to say, if you look at the Democratic convention and its speeches and the Harris-Walz rallies, if the MAGA aesthetic is reality TV, if it's The Apprentice, the Democratic one is Friday Night Lights.

I don't think of that as a Democratic TV show per se. It was very famously a red and blue TV show in terms of who the characters it featured. But that message that we are a team, that by including everyone, even that geek who doesn't seem like he would be a good field goal kicker, we become stronger, and that makes us better off overall, there's a narrative to that that you can use.

Partly the answer is not figuring out “How can we be Donald Trump?” because you've seen others, particularly Ron DeSantis, try that and then looking ridiculous and failing. It is: What is our thing that is emotionally as powerful to who we need to speak to?

JKA: How do you think that the major changes in TV and maybe even the media in general over the last decade have affected the way he campaigns? Because 2016 is actually quite different from 2024 in terms of our television landscape and our social media landscape.

JP: In 2016, I do think that TV news and cable news particularly were just so much bigger in that TV news would amplify whatever provocation he had made on Twitter. And there were all the rallies, which at this point were this new, unpredictable thing that we hadn't seen before, and cable news channels, their whole job is they have to fill up 24 hours a day with things that will keep people from turning the channel. And so not just Fox, but CNN, MSNBC would have him on their screen all the time.

Now media is even more fragmented and TV news isn't necessarily handling the rallies the way it used to before. So Trump is doing more friendly interviews on Fox, that sort of thing. He's still doing the rallies, but the scale and the impressiveness is not necessarily there, and they're certainly not being covered wall-to-wall the way they were before. On the other hand, we're now in the age of podcasts and he's been doing a lot more with influencers and young, right-wing, YouTube and podcast personalities. There's been a lot more niche targeting of stuff like that. There's been more sort of micro, because the story of media in our era is always fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces.

And his original campaign benefited to the extent that cable news was much more important than big newspapers or broadcast news outlets, and there was a whole conservative media apparatus that could build them up. And now even that conservative media apparatus has atomized since then. There are all the podcasts, there's YouTube, there are competitors to Fox News, your Newsmax and so on. I think his campaign is using that more in the general election.

One other interesting thing that he did this year, particularly during the Republican primary, was to use the various trials that he was in as sort of a running TV show because networks couldn't get cameras into the courtroom, so they were scrambling for whatever live video that they could get, and the live video that they could get would be Trump coming out after the day's events and standing in front of the barricades and talking a little bit about how this is the greatest witch hunt the country has ever seen, and then talking about inflation and immigration and basically going into his stump pitch, and it just kind of sucked up all the oxygen that might've supported anyone who was trying to beat him in the Republican primary.

I will say it's not like nothing has changed for him, honestly. As somebody who has watched his media evolution over decades and then especially during his campaigns and presidency, he does often seem lower-energy, often tired in front of the cameras for whatever reasons at his trials, at his rallies, in the interviews, but he still has that gut instinct for just how the attention economy works.

JKA: You were mentioning the podcasts and that’s so interesting to me. I feel like I don’t see him as much anymore, which is very nice, but it also gives me the impression that he's not out there doing as much as he used to, when really it could just be my own media diet.

JP: If you are not in his target demographic, you might not be seeing him anymore, but he might be getting seen by a lot of young conservative men. That is a difference both in the media environment and in the energy around his campaign. One thing he benefited from in 2016 was that his run for president was so novel and surprising that it became the number one show on TV. We've been talking a lot about cable news and the rallies, but it wasn't just that. It's like sitcoms would have jokes about him and obviously every late-night monologue was about him. Just any broadcast that wanted to get some piece of the watercooler conversation had some element of: Did you hear the thing Donald Trump said?

One thing he benefited from in 2016 was that his run for president was so novel and surprising that it became the number one show on TV.

And so it really was like, even if you weren't very political or even if you weren't a Republican, you were seeing him heard and talked about just everywhere. And that is not as true now, partly because the media environment's changed, partly because the political strategy has changed, and partly because his show and his shtick is not as new or surprising anymore. I think it's kind of interesting, by the way, that one line of attack that [Harris] has settled on for him is: It's the same old tired argument.

It goes to the heart of Donald Trump's existence as a celebrity. You can say, this guy is a fascist, he's a sexist, he's a racist. The dagger into his heart is saying, “You don't got it anymore. Your act is boring. You're washed up. You’re not The Apprentice, you’re The Celebrity Apprentice, season 14.” I don't know that that's necessarily going to work for her, but that is something that hits at the core engine of what makes Donald Trump, Donald Trump.

You can say, this guy is a fascist, he's a sexist, he's a racist. The dagger into his heart is saying, “You don't got it anymore. Your act is boring. You're washed up. You’re not ‘The Apprentice,’ you’re ‘The Celebrity Apprentice,’ season 14.”

JKA: There has been truly so much excitement for her. Where do you think that comes from culturally? Is it just the plot switch that we had? How do you think she hijacked this narrative from him?

JP: She was the first politician in nine years or whatever who was able to become the main character in American politics rather than Donald Trump. Joe Biden was never that through four years as president, whatever he did may have accomplished policy-wise. This is not like a knock on him governing, but just as a media figure, his election was in reaction to Donald Trump, and of course Donald Trump was still out there getting headlines for this and that the entire time Biden was president.

Finally [with Harris], there was somebody who had a version of the thing that Donald Trump had in 2015, which was being the new thing that people are interested in. And I think that her campaign, partly through serendipity and the benevolence of the TikTok teens and Charli XCX and all that, but also I think through some execution, capitalized on that, kept that going and inhaled all the oxygen.

For the month or so after her introduction, they recognized after you had this campaign in which so many people said that they were depressed at having the same choices as they did the last time, they were able to have this branding of the new product and were really able to take advantage of that.

How Kamala Became Brat and Mother

The presidential hopeful is harnessing the power of pop princesses Charli XCX and Chappell Roan, not to mention Gen Z internet culture. The result? An intergenerational femininomenon.

JKA: You mentioned the Friday Night Lights of it all. I'm wondering if you have any other thoughts on how the anti-hero is kind of out now. Your book makes the point that the anti-hero trend in television helped Trump’s rise. But we're into Ted Lasso now. Do you think that has any bearing on Donald Trump as a figure?

JP: It's probably affected the way that his campaign has run to some extent. In other words, I think there's less overt messaging about “I'm the asshole who it takes to get the job done.” I mean, they actually in 2020 and 2016 ran campaign ads that said—they didn't use the word asshole, but more like “It takes a tough guy.” He may not be the nicest guy, but it takes a tough guy to do the job. And so there's less overt stuff like that [now]. On the other hand, at some point, the analogies between the TV universe and a presidential election, which is still just generally a binary choice, kind of breaks down. And there is still an anti-hero element to his campaigning because there is still a “We love the anti-hero” element to his coalition.

Meaning, yes, I think that this is right now more of a Ted Lasso era than a Tony Soprano, Walter White era. But on the other hand, even now, you still have a lot of people who love Breaking Bad, et cetera, and you still have Trump doing things like monetizing his Georgia courthouse mugshot, which he's used like the Johnny Cash flipping-the-bird photo.

JKA: You've studied his media playbook so much. What do you think it takes to defeat him?

JP: In any election, the thing that it takes to win often changes. I think it is important not to let him dominate you because so much of his persona is about the performance of dominance. If you don't counter-program him and provide a story that is your story, which maybe is that “I am the new thing that's going to bring this country forward and move us on from this tired old stuff that we're all sick of,” if you leave a vacuum, then you're giving him a chance to fill it and he might fill it with something that ends up being inadvertently helpful to you, but he might not. It's always going to be putting on a show. You have to figure out what your show is and what its elevator pitch is, and you have to put on that show and command the attention of the audience because that's how you guarantee that you can tell your story rather than it getting told for you.

JKA: One final question: How do you think he has changed the presidential campaign game forever? What is his legacy in terms of media management?

JP: That's a good question because I can talk about stuff that he did, but there's also what can work for what can and can't work for everybody else. But I think he's shown the dangers of excessive caution, media-wise. I don't want to say that he's proven that there's no such thing as bad attention, but he has taught that there's maybe nothing worse than no attention, and people have learned from that, whether they can successfully apply the lesson or not.

This exchange has been condensed and edited for clarity.

I love "Audience of One," and always want to know how James Poniewozik is responding to the latest political developments through the lens of TV. So this Q&A is everything I wanted and more.

I saw Trump's star on the Walk of Fame last week and was like, How as it not been cracked?! Then again: He is a creation of Hollywood. So...it makes sense.